In a previous “What the F?” post, I discussed the NRSA fellowship and why you should consider writing one. The next step in the fellowship application process is to decide when to apply. The usual answer is “as soon as possible”. The NIH wants to support your training, so it is best to apply as early in your training as you can. But what factors determine the best time for you?

Do I Need All the Data?

Applicants often worry that they need to be an expert in their area of research and have a mountain of data before they can apply. However, NRSA fellowships are designed to support your training as a scientist, not the science itself. Good science does need to be presented, but the training plan is the most important factor when reviewing fellowship applications. Reviewers should be confident that you have a basic understanding of your science and what question(s) you are trying to answer, but you need not be an expert on the topic prior to submitting. That’s what the training is for! When submitting a fellowship application, it is okay, and often expected, that you will use data and/or findings from a current or former lab mate’s work. Just be sure to give credit to the team.

When are Applications Accepted?

What else goes into determining when to begin the application process? NIH due dates are a great first start. Fellowship applications have three submission cycles with standard due dates on the 8th of April, August, and December. After submission, it takes an NIH institute 5-9 months to review an application and announce whether or not it will be funded (see table below). So, if you want your funding to start April 1st of next year, you must submit your application nine months prior on August 8th of this year.

How Much Time for Writing?

In addition to the 5 – 9 months needed for NIH review, you need to determine how much time to allocate to the writing process. In my experience, it takes an applicant 3-6 months to gather the information required to write, review, and edit a well-thought-out application. Questions to consider when determining how much time to schedule for writing include:

- What amount of time do coursework and research take in my week?

- Are there other regular commitments I need to devote time to such as lab meetings, journal clubs, etc.?

- Does my lab, collaborator, and/or institution have descriptive text available on equipment, facilities, animal use, etc. or do I need to create original text?

- How available is my PI (and collaborators) to provide feedback and edits? How far in advance do they need a draft to provide comments? How much time do I need to make the recommended edits?

- How much time do those I’d like to ask to write letters of recommendation need to do so? [Voice of Experience: Ask them at least 3 months in advance.]

When the 5-9 months it takes for the NIH to process a Notice of Award is added to the 3-6 months to write, you’ll find you need to begin writing a fellowship application 8-15 months prior to when you would like your fellowship funding support to begin (see graphic below). That is, of course, if your initial application is funded, which is never guaranteed.

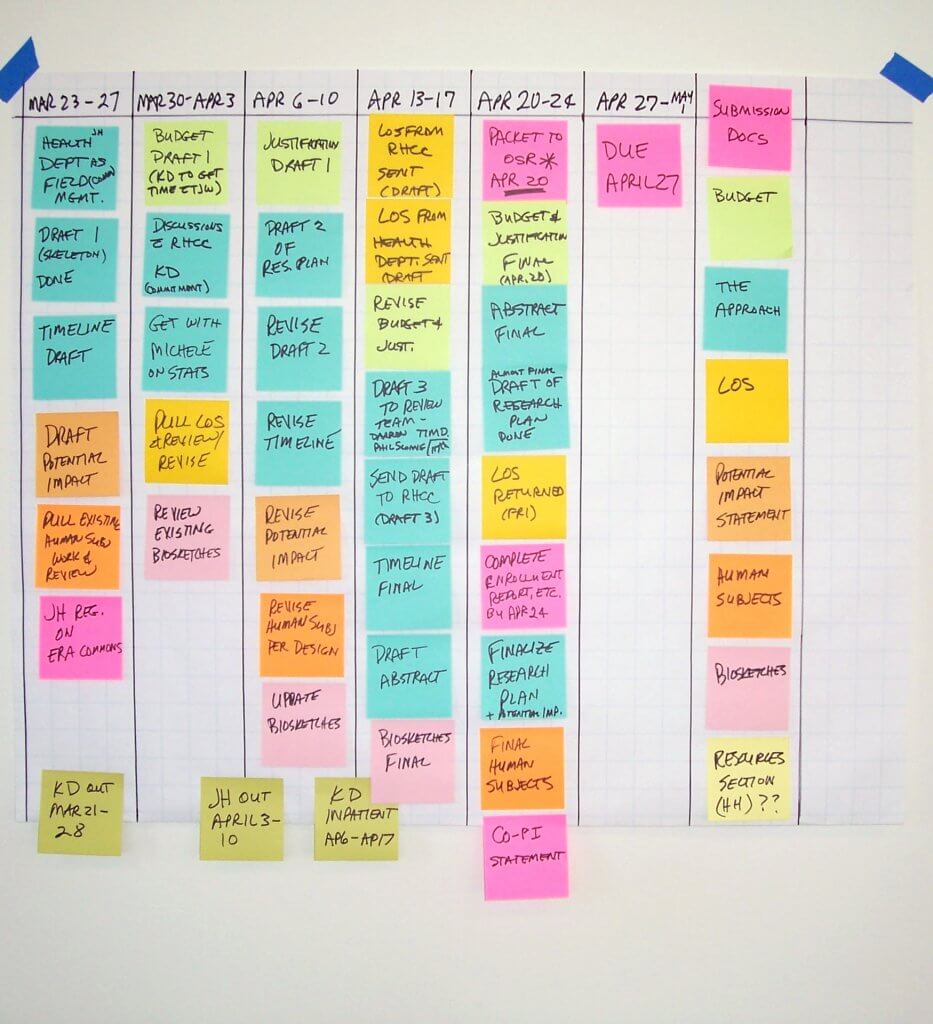

How Do I Develop a Timeline?

How Do I Develop a Timeline?

I find it helps to start at the end and work backwards. In an ideal world, when would you want this funding to begin? It’s helpful to consider what funding sources are currently available to you. Are you on a training grant that ends in 10 months? Does your PI have dedicated funding on a research grant that must be expensed over the next 20 months? Once you determine that ideal start date and how much time you need to write, work backwards 8-15 months and that is when you should target starting your application.

Finally, here are a few additional unique items each population of biomedical trainees (doctoral candidates, dual degree students, and postdoctoral fellows) might also want to consider.

Doctoral Students

- F31 and F31-Diversity guidelines require that a doctoral student have passed their qualifying exam prior to when funding begins. You may submit prior to completing your qualifying exam, but you must have completed and passed it prior to beginning your award.

- Does your graduate program offer a grant writing course that will help guide you in the process? If yes, you may want to plan your submission date for after completion of this course.

- Doctoral students are eligible for up to 5 years of NRSA support, which is cumulative of time appointed to NRSA funded training grants (typically T32) and support from an individual fellowship. Does your institution/program typically fund a portion of your training via a T32 appointment? Does that impact when the ideal time for you to apply is?

MD/PhD (and other dual-degree seeking) Students

- F30 (Institution with MSTP or Institution without MSTP) guidelines require that MD/PhD students must apply within 48 months of matriculation to their dual-degree program. This is 48 months from the start date (typically orientation) of the earlier of the MD/PhD or MD program, if on different schedules. This policy may be slightly different for other dual degree programs (i.e. AUD/PhD, DDS/PhD, etc.).

- F30 guidelines also stipulate that at least 50% of time on fellowship support must be for training during the graduate years. If you are in a 2-4-2 program and would like the final two years of medical school training supported by your fellowship, you would need to apply no later than the first semester of your second year of graduate school so that funding could begin in your third year (remember the 8-15 months we discussed above to turn a grant around).

- Dual degree students are eligible for up to 6 years of NRSA funding, cumulative of NRSA T32 and fellowship support. The layout of your program may dictate the best time to apply and/or the number of years of support to request.

Postdoctoral Trainees

- For postdoctoral trainees, the answer to when to apply is simple. Now. The NRSA provides three years of funding for postdoc training, cumulative of both time you have been appointed to a T32 institutional training grant as a post-doc and time funded by your F32 postdoctoral fellowship. [Quick tip: The cumulative amount of time appointed to a NRSA funding source restarts after completion of pre-doc training.] On average a postdoc experience is 4-5 years and as stated above, it takes 8-15 months to write, submit and receive funding, so you will want to start writing as soon as possible in order to maximize the amount of funding available to you.

- A question to consider as a postdoc is when to submit your K-award post-F32 submission. Check out these blogs for more information on that topic.

SBIR/STTR grants are structured and reviewed largely like R01s, with an overall impact score and scores for significance, investigator(s), innovation, approach, and environment. The business plan should be integrated with the research plan. For a Phase I application, this might mean a “future directions” or “planned Phase II” section explaining that upon completion of Phase I, you will move from prototype to production, request regulatory approval, or start selling the device. Phase II applications often include sections detailing methods of production, marketing plans, expected revenue stream, or other commercialization plans.

SBIR/STTR grants are structured and reviewed largely like R01s, with an overall impact score and scores for significance, investigator(s), innovation, approach, and environment. The business plan should be integrated with the research plan. For a Phase I application, this might mean a “future directions” or “planned Phase II” section explaining that upon completion of Phase I, you will move from prototype to production, request regulatory approval, or start selling the device. Phase II applications often include sections detailing methods of production, marketing plans, expected revenue stream, or other commercialization plans.

If your fellowship isn’t funded, it’s an opportunity for you to gather feedback on your science and refine your writing style in a resubmission or in future grants. You can still list it on your CV to let future employers know you took the initiative to seek funding and gained skills in grant writing.

If your fellowship isn’t funded, it’s an opportunity for you to gather feedback on your science and refine your writing style in a resubmission or in future grants. You can still list it on your CV to let future employers know you took the initiative to seek funding and gained skills in grant writing. The first rejection of any type hurts the most: There is no magic pill to lessen the blow of the first rejection. Going into my faculty position with my successful K99/R00, I thought securing my first R01 would be challenging, but not impossible. Needless to say, when my first R01 submission swung the other way and scored terribly, it was a brutal awakening. I have put in numerous grants now and while annoyed and concerned about my lack of R01 funding, my recovery time with each unfunded grant has decreased substantially.

The first rejection of any type hurts the most: There is no magic pill to lessen the blow of the first rejection. Going into my faculty position with my successful K99/R00, I thought securing my first R01 would be challenging, but not impossible. Needless to say, when my first R01 submission swung the other way and scored terribly, it was a brutal awakening. I have put in numerous grants now and while annoyed and concerned about my lack of R01 funding, my recovery time with each unfunded grant has decreased substantially.

Your grants manager is a key person in ensuring smooth submission of your grant. Here’s what every grants manager wants you to know:

Your grants manager is a key person in ensuring smooth submission of your grant. Here’s what every grants manager wants you to know: